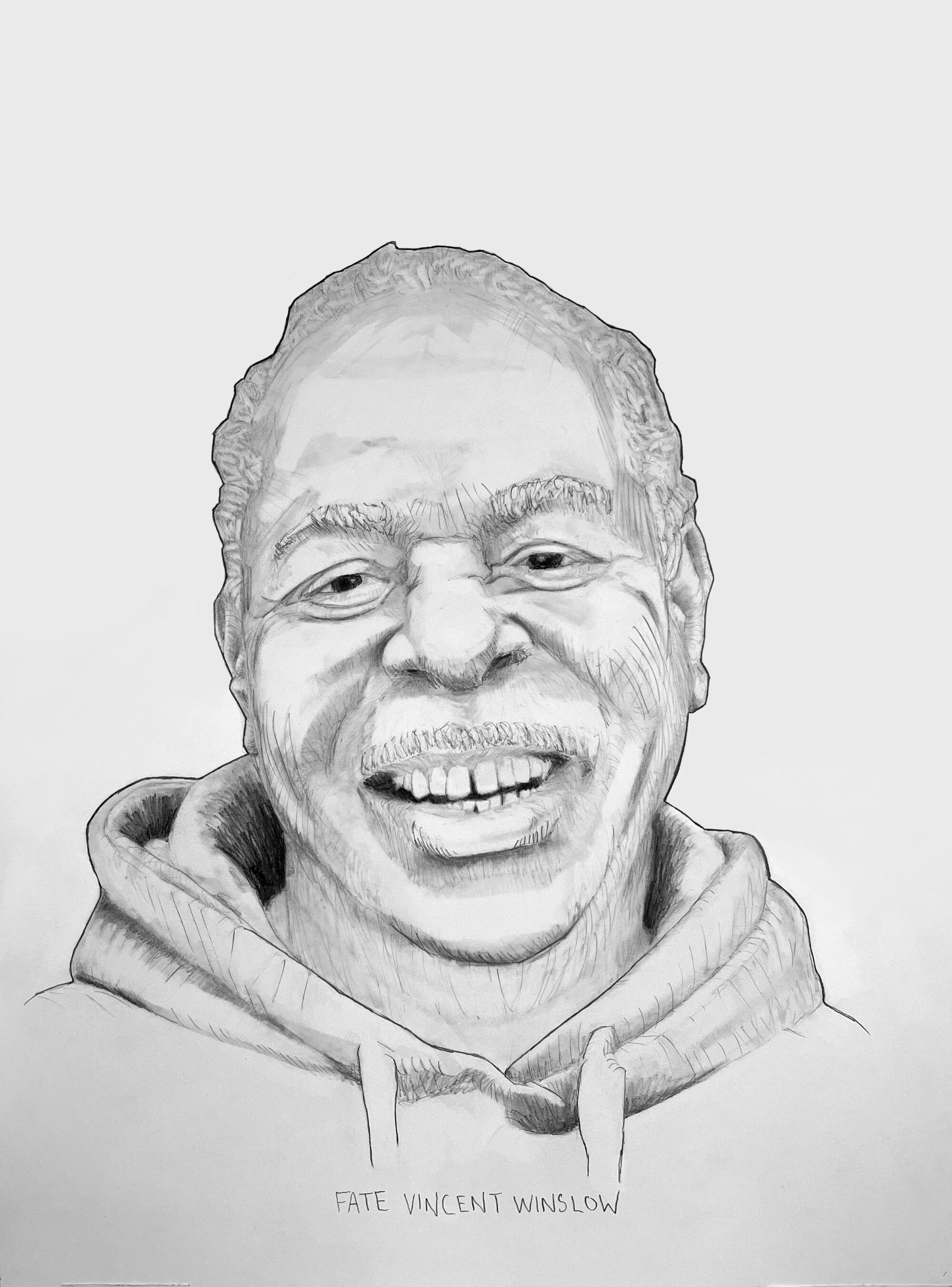

Fate Vincent Winslow

"Fate Vincent Winslow," graphite on paper, 12 3/4″ × 17″. 2022

Fate Vincent Winslow

Fate Vincent Winslow was the target of a racist policing and criminal justice system

Fate Vincent Winslow was unhoused when he was arrested on the evening of Sept. 5, 2008 in Shreveport, Louisiana after being baited into selling an undercover police officer marijuana. During his arraignment, he was represented by an inadequate public defender who gave a 30-second opening statement, called no witnesses and offered no evidence for Winslow’s defense.

The public defender did not point out that Winslow was not a drug dealer but only sold because he needed money for food. Nor did he point out that the white drug dealer he was working for was also apprehended at the same moment by undercover police and was never arrested. Winslow was convicted by a racially split jury (ten white jurors versus two black) and spent the next twelve years of his life at the Angola maximum-security prison (a former slave plantation). In May of 2021, just a few months after his release, Winslow was murdered. Those who knew him described his good natured, positive, and upbeat spirit.

Winslow’s story illuminates the devastating reality of structural poverty and structural racism in the United States.

Published on April 8, 2023, Updated March 18, 2024

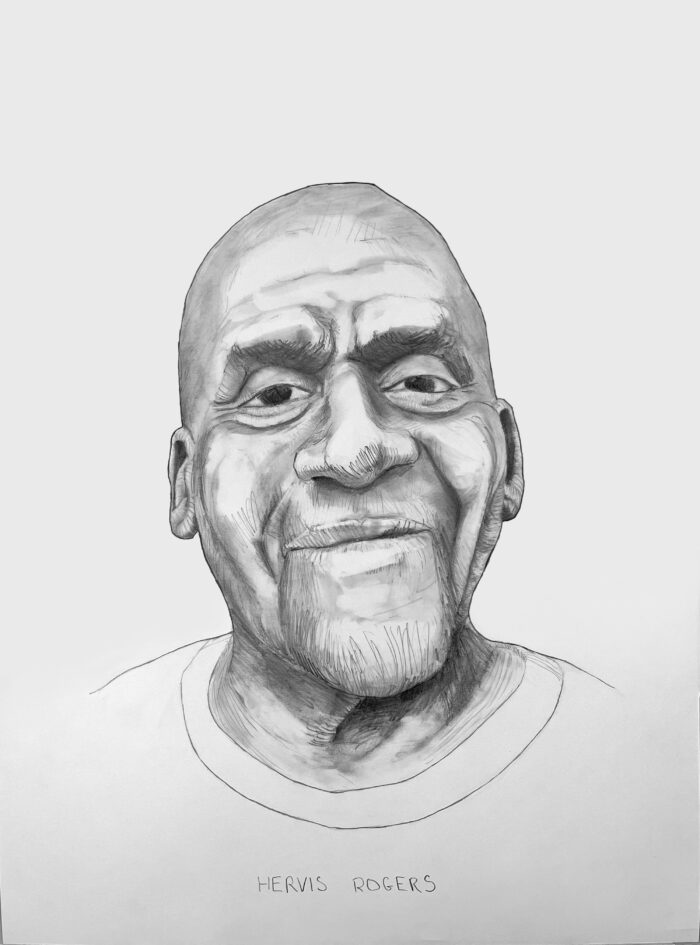

Hervis Rogers

Hervis Rogers

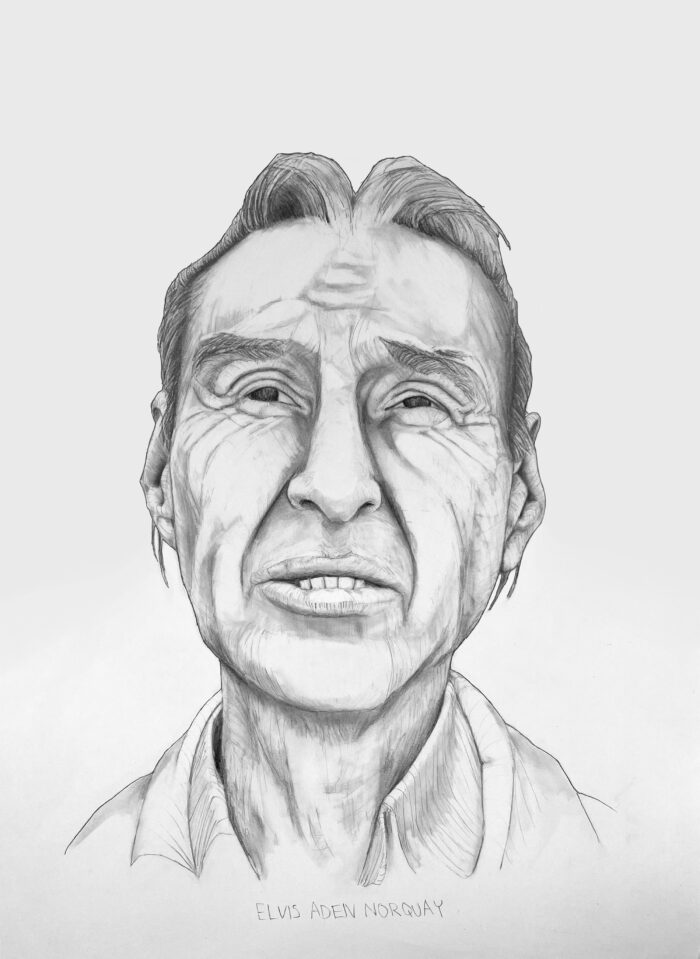

Elvis Aden Norquay

Elvis Aden Norquay