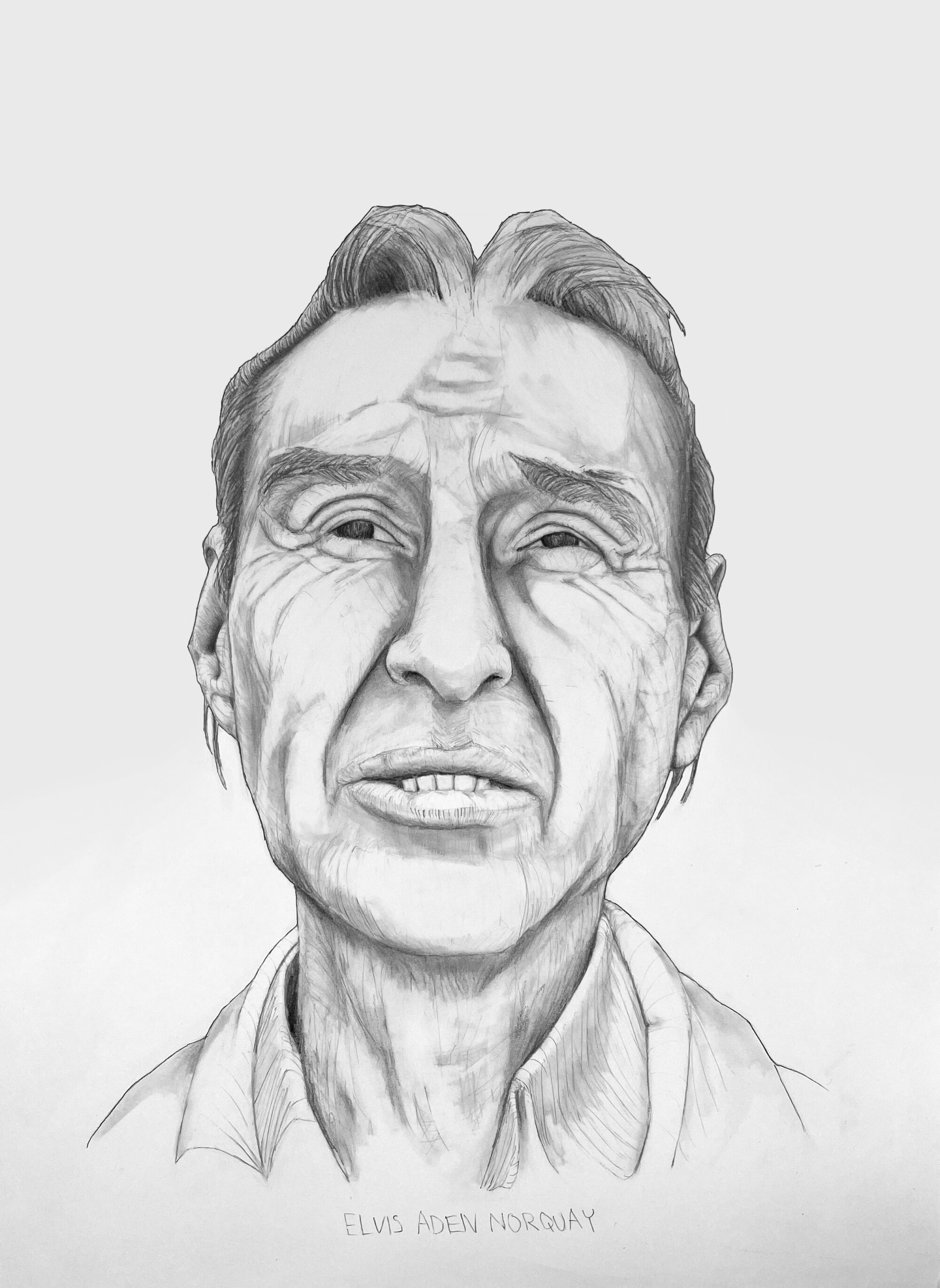

Elvis Aden Norquay

"Elvis Aden Norquay," graphite on paper, 12 3/4"″ × 17″. 2022

Elvis Aden Norquay

Elvis Norquay and Indigenous communities fought back against Republican’s voter suppression efforts in North Dakota

When Elvis Norquay went to vote in the 2014 general election in North Dakota, he was caught off guard. For the first time in thirty years of voting, his tribal ID card was rejected at his polling site. After the 2012 election and 3,000-vote statewide victory for the former Democratic U.S. Senator Heidi Heidkamp, the Republican legislature passed a voter ID law that denied 5,000 tribal residents their right to vote because they didn’t have a mailing address on their IDs.

Many indigenous people in rural parts of the state use post office boxes if their local government hasn’t assigned residential addresses for their homes. “It’s my right to vote for whomever I want. I shouldn’t be turned away just because I didn’t have my address listed,” Norquay told Indian Country Today in 2016. Norquay and indigenous organizers fought back. They began a multiyear advocacy effort to reverse the discriminatory laws, culminating in court battles that led to some access being restored for indigenous people.

Norquay passed away in May 2021, but his legacy of protecting voting rights for marginalized people, particularly indigenous communities, continues to ensure that all of us have equal access to the ballot.

Published on April 10, 2023, Updated March 18, 2024

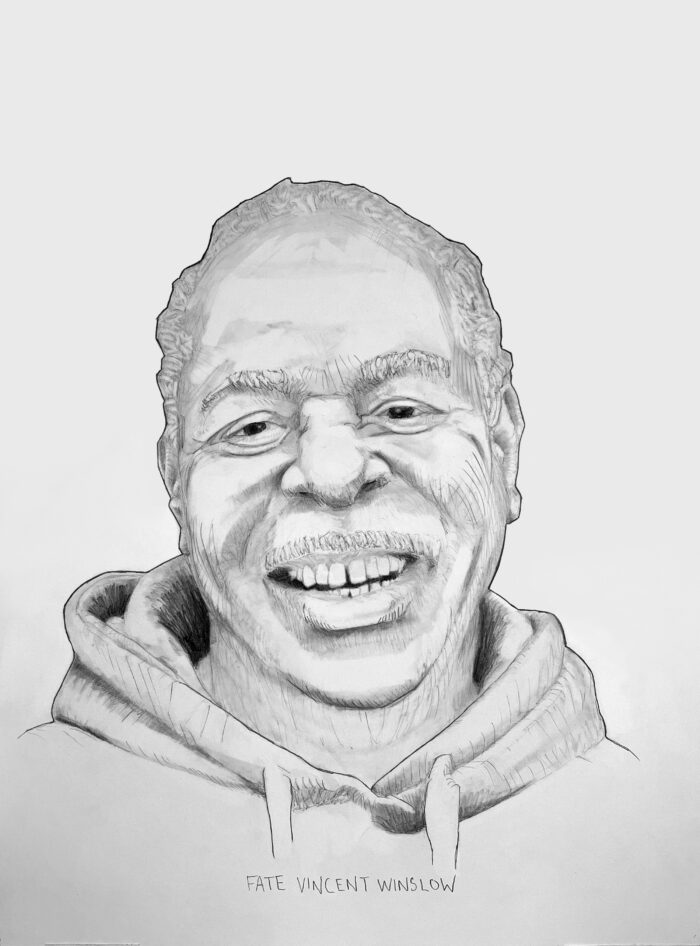

Fate Vincent Winslow

Fate Vincent Winslow

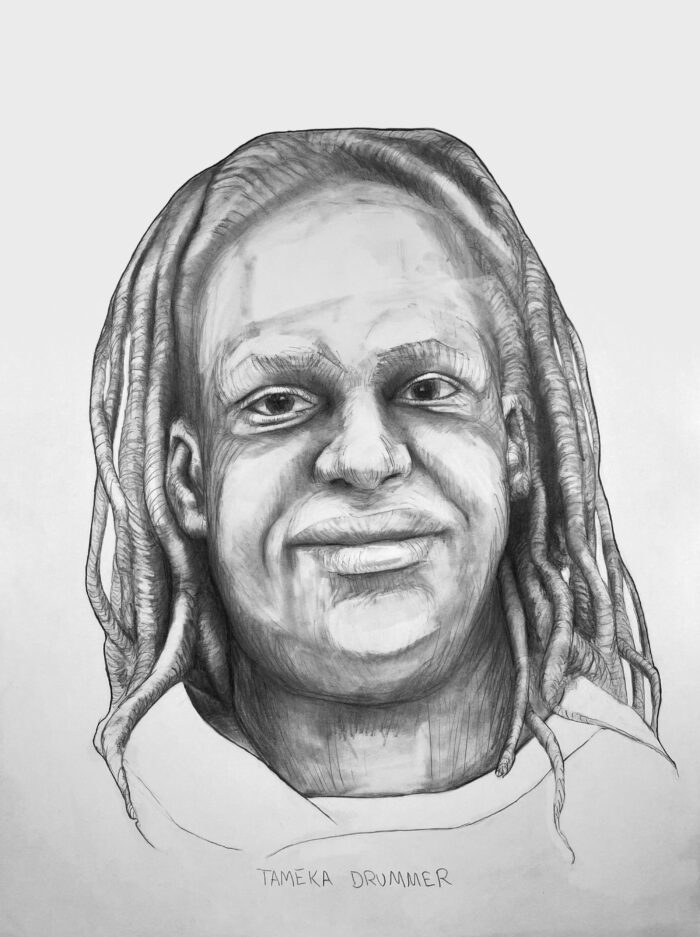

Tameka Drummer

Tameka Drummer