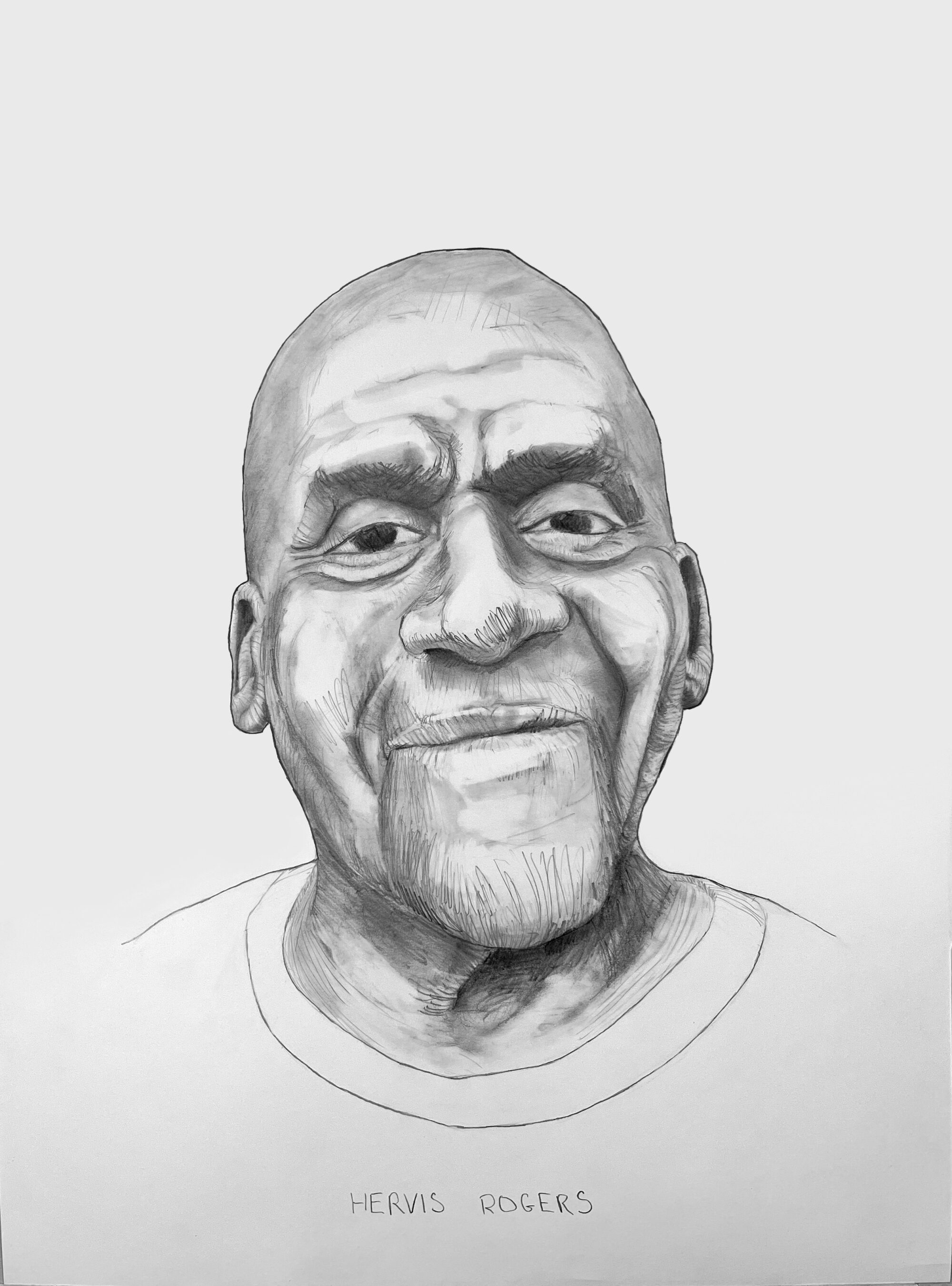

Hervis Rogers

"Hervis Early Rogers," graphite on paper, 12¾″ × 17″. 2022

Hervis Rogers

For Hervis Rogers, criminal justice and voter suppression fused on election night

During the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, Hervis Rogers arrived at his polling place at Texas Southern University in Houston, TX and experienced long wait lines, fewer voting machines and other explicit forms of voter suppression enacted by the Harris County Republican Party. He was the last person in line to vote and debated whether to stay in what would turn out to be a six-hour wait in line.

Rogers suspected that the long wait time was orchestrated to deter voters from staying and decided to wait it out. He was also completing the final months of a nearly 16-year parole period and voted not knowing he was ineligible while on parole. The Texas attorney general ordered Roger’s arrest, setting bail at $100,000. A year later, a judge dismissed all so-called “voter-fraud” charges against him. Rogers is one of many formerly incarcerated people who’ve had their voting rights taken away.

Maine and Vermont are currently the only states where the voting rights of formerly incarcerated people are protected.

Published on April 5, 2023, updated March 18, 2024

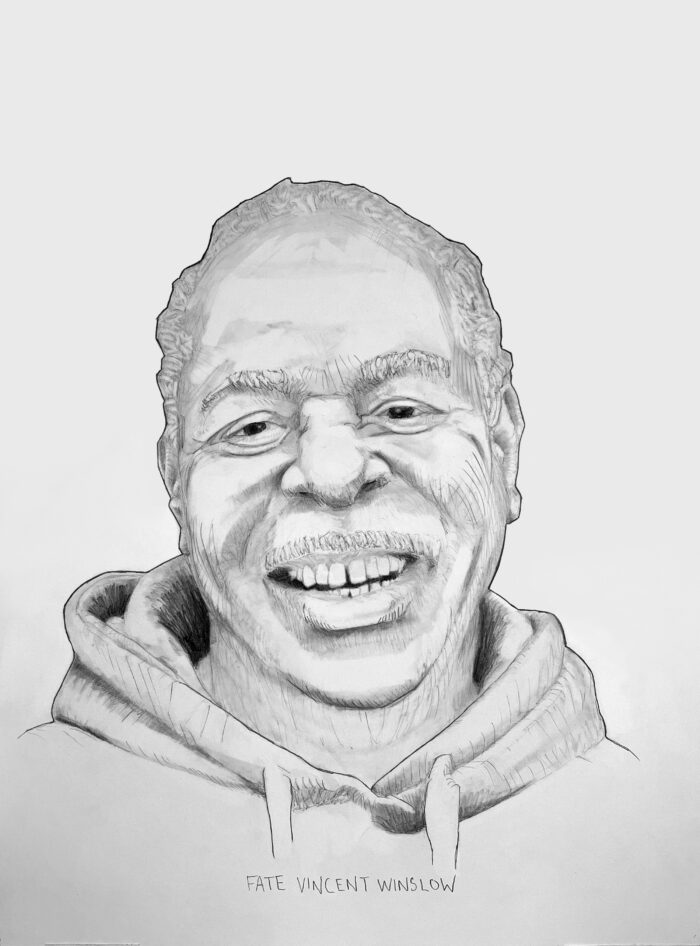

Fate Vincent Winslow

Fate Vincent Winslow